|

|

|

Sound mixers (AKA sound desks, sound consoles or sound

boards) are amongst the most common type of equipment in the world of audio

production. Every sound operator must know what a sound mixer is and how to use

it. The tutorials below cover the general layout and functions of sound mixing

devices.

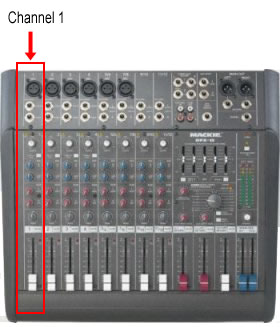

Each input source comes into the mixer through a channel. The more channels

a mixer has, the more sources it can accept. The following examples show some

common ways to describe a mixer's compliment of channels:

|

12-channel |

12 input channels. |

|

16x2 |

16 input channels, 2 output channels. |

|

24x4x2 |

24 input channels, 4 subgroup channels and two output

channels. |

Input Channels

Input ChannelsOn most sound desks, input channels take up most of the space. All those

rows of knobs are channels. Exactly what controls each channel has depends on

the mixer but most mixers share common features. The list below details the

controls available on a typical mixer channel.

Input Gain / Attenuation: The level of the signal as it enters the

channel. In most cases this will be a pot (potentiometer) knob which adjusts

the level. The idea is to adjust the levels of all input sources (which will be

different depending on the type of source) to an ideal level for the mixer.

There may also be a switch or pad which will increase or decrease the level by

a set amount (e.g. mic/line switch).

Phantom Power: Turns phantom power on or

off for the channel.

Equalization: Most mixers have at least two EQ controls (high and low

frequencies). Good mixers have more advanced controls, in particular, parametric

equalization.

See also: Audio

equalization.

Auxiliary Channels: Sometimes called aux channels for short,

auxiliary channels are a way to send a "copy" of the channel signal

somewhere else. There are many reasons to do this, most commonly to provide

separate monitor feeds or to add effects (reverb etc).

Pan & Assignment: Each channel

can be panned left or right on the master mix. Advanced mixers also allow the

channel to be "assigned" in various ways, e.g. sent directly to the

main mix or sent only to a particular subgroup.

Solo / Mute / PFL: These switches control how the channel is

monitored. They do not affect the actual output of the channel.

Channel On / Off: Turns the entire channel on or off.

Slider: The level of the channel signal as it leaves the channel and

heads to the next stage (subgroup or master mix).

Larger sound desks usually have a set of subgroups, which provide a

way to sub-mix groups of channels before they are sent to the main output mix.

For example, you might have 10 input channels for the drum mics

which are assigned to 2 subgroup channels, which in turn are assigned to the

master mix. This way you only need to adjust the two subgroup sliders to adjust

the level of the entire drum kit.

The first point of each channel's pathway is the input socket, where the

sound source plugs into the mixer. It is important to note what type of input

sockets are available — the most common types are XLR,

6.5mm

Jack and RCA.

Input sockets are usually located either on the rear panel of the mixer or on

the top above each channel.

There are no hard-and-fast rules about what type of equipment uses each type

of connector, but here are some general guidelines:

|

XLR |

Microphones and some audio devices. Usually balanced audio, but XLRs can also accommodate unbalanced

signals. |

|

6.5mm Jack |

Musical instruments such as electric guitars, as well as

various audio devices. Mono jacks are unbalanced, stereo jacks can be either

unbalanced stereo or balanced mono. |

|

RCA |

Musical devices such as disc players, effects units, etc. |

Note: For more information see Audio Connections.

The level of an audio signal refers to the voltage level of the

signal. Signals can be divided into three categories: Mic-level

(low), line-level (a bit higher) and loudspeaker-level (very

high). Microphones produce a mic-level signal,

whereas most audio devices such as disc players produce a line-level signal.

Loudspeaker-level signals are produced by amplifiers and are only appropriate

for plugging into a speaker — never plug a loudspeaker-level signal into

anything else.

Sound mixers must be able to accommodate both mic-level

and line-level signals. In some cases there are two separate inputs for each

channel and you select the appropriate one. It is also common to include some

sort of switch to select between inputs and/or signal levels.

Input

Sockets and Controls

Input

Sockets and ControlsThe example on the right shows the input connections on a typical mixer.

This mixer has two input sockets — an XLR for mic-level

inputs and a 6.5mm jack for line-level inputs. It also has a pad button

which reduces the input level (gain) by 20dB. This is useful when you have a

line-level source that you want to plug into the mic

input.

Some mixers also offer RCA inputs or digital audio inputs for each channel.

Some mixers provide different sockets for different channels, for example, XLR

for the first 6 channels and RCA for the remainder.

When a signal enters the mixer, one of the first controls is the input gain.

This is a knob which adjusts the signal level before it continues to the main

parts of the channel. The input gain is usually set once when the source is

plugged in and left at the same level — any volume adjustments are made by the

channel fader

rather than the gain control.

Set the gain control so that when the fader is at 0dB the signal is peaking

around 0dB on the VU

meters.

Phasing: Some equipment and cables are wired with

different phasing, that is, the wires in the cable which carry the signal are

arranged differently. This will kill any sound from that source. To fix

this problem, some mixers have a phase selector which will change the

phasing at the input stage.

Phantom Power: Some mixers have the option to provide a small voltage

back up the input cable to power a microphone or other device. See Phantom Power for

more information.

Most

mixers have some of sort equalization controls for each channel. Channel

equalizers use knobs (rather than sliders), and can be anything from simple

tone controls to multiple parametric controls.

Most

mixers have some of sort equalization controls for each channel. Channel

equalizers use knobs (rather than sliders), and can be anything from simple

tone controls to multiple parametric controls.

Note: For more general information about equalization see Audio Equalizers.

The first example on the right is a simple 2-way equalizer, sometimes

referred to as bass/treble or low/high. The upper knob adjusts high frequencies

(treble) and the lower knob adjusts low frequencies (bass). This is a fairly

coarse type of equalization, suitable for making rough adjustments to the

overall tone but is not much use for fine control.

This

next example is a 4-way equalizer. The top and bottom knobs are simple high and

low frequency adjustments (HF and LF).

This

next example is a 4-way equalizer. The top and bottom knobs are simple high and

low frequency adjustments (HF and LF).

The middle controls consist of two pairs of knobs. These pairs are parametric

equalizers — each pair works together to adjust a frequency range chosen by

the operator. The brown knob selects the frequency range to adjust and the

green knob makes the adjustment.

The top pair works in the high-mid frequency range (0.6KHz

to 10KHz), the lower pair works in the low-mid range (0.15 to 2.4KHz).

The "EQ" button below the controls turns the equalization on and

off for this channel. This lets you easily compare the treated and untreated

sound.

It is common for mixers with parametric equalizers to combine each pair of

knobs into a single 2-stage knob with one on top of the other. This saves space

which is always a bonus for mixing consoles.

If the mixer provides good parametric equalization you will usually find

that these controls are more than adequate for equalizing individual sources.

If the mixer is limited to very simple equalization, you may want to use

external equalizers. For example, you could add a graphic equalizer to a

channel using the insert feature.

In many situations you will use additional equalization outside the mixer.

In live sound situations, for example, you will probably have at least one

stereo graphic equalizer on the master output.

Most sound desks include one or more auxiliary channels (often

referred to as aux channels for short). This feature allows you to send

a secondary feed of an input channel's

audio signal to another destination, independent of the channel's main output.

The example below shows a four-channel mixer, with the main signal paths

shown in green. Each input channel includes an auxiliary channel control knob —

this adjusts the level of the signal sent to the auxiliary output (shown in

blue). The auxiliary output is the sum of the signals sent from each channel.

If a particular channel's auxiliary knob is turned right down, that channel is

not contributing to the auxiliary channel.

In the example above, the auxiliary output is sent to a monitoring system.

This enables a monitor feed which is different to the main output, which can be

very useful. There are many other applications for auxiliary channels,

including:

Mixers are not limited to a single auxiliary channel,

in fact it is common to have up to four or more. The following example has two

auxiliary channels — "Aux 1" is used for a monitor and "Aux

2" is used for an effects unit.

Note that the monitor channel (Aux 1) is "one way", i.e. the

channel is sent away from the mixer and doesn't come back. However the Aux 2

channel leaves the mixer via the aux send output, goes through the

effects unit, then comes back into the mixer via the aux return input.

It is then mixed into the master stereo bus.

The

auxiliary output from each channel can be either pre-fader or post-fader.

The

auxiliary output from each channel can be either pre-fader or post-fader.

A pre-fader output is independent of the channel fader, i.e. the

auxiliary output stays the same level whatever the fader is set to.

A post-fader output is dependent on the fader level. If you turn the

fader down the auxiliary output goes down as well.

Many mixers allow you to choose which method to use with a selector button. The

example pictured right shows a mixer channel with four auxiliary channels and

two pre/post selectors. Each selector applies to the two channels above it, so

for example, the button in the middle makes both Aux 1 and Aux 2 either

pre-fader or post-fader.

One of the last sets of controls on each channel,

usually just before the fader, is the channel assign and pan.

Pan

PanAlmost all stereo mixers allow you to assign the amount of panning. This is

a knob which goes from full left to full right. This is where the channel

signal appears on the master mix (or across two subgroups if

this is how the channel is assigned). If the knob is turned fully left, the

channel audio will only come through the left speaker in the final mix. Turn

the knob right to place the channel on the right side of the mix.

This option may be absent on smaller mixers but is quite important on large

consoles. The assign buttons determine where the channel signal is sent.

In many situations the signal is simply sent to the main master output. In

small mixers with no assign controls this happens automatically.

However you may not want a channel to be fed directly into the main mix. The

most common alternative is to send the channel to a subgroup first. For

example, you could send all the drum microphones to their own dedicated

subgroup which is then sent to the main mix. This way, you can adjust the

overall level of all the drums by adjusting the subgroup level.

In

the example pictured right, the options are:

In

the example pictured right, the options are:

For stereo applications it is common to use subgroups in pairs to maintain

stereo separation. For example, it is preferable to use two subgroups for the

drums so you can pan the toms and cymbals from left to right.

You can assign the channel to any combination of the available options.

In some cases you may not want the channel to go to the main mix at all. For

example, you may have a channel set up for communicating with the stage via an aux

channel. In this case you don't assign the channel anywhere.

PFL

means Pre-Fade Listen. It's function is to do

exactly that — listen to the channel's audio at a point before the fader takes

effect. The PFL button is usually located just above the channel fader. In the

example on the right, it's the red button (the red LED lights when PFL is engaged).

PFL

means Pre-Fade Listen. It's function is to do

exactly that — listen to the channel's audio at a point before the fader takes

effect. The PFL button is usually located just above the channel fader. In the

example on the right, it's the red button (the red LED lights when PFL is engaged).

Note: PFL is often pronounced "piffel".

When you press the PFL button, the main monitor output will stop monitoring

anything else and the only audio will be the selected PFL channel(s). This does

not affect the main output mix — just the sound you hear on the monitor bus. Note that all

selected PFL channels will be monitored, so you can press as many PFL buttons

as you like.

PFL also takes over the mixer's VU meters.

PFL is useful when setting the initial input gain

of a channel, as it reflects the pre-fade level.

PFL is similar to the solo button. There are two differences:

Each channel has it's

own fader (slider) to adjust the volume of the channel's signal before it is

sent to the next stage (subgroup or master mix).

Each channel has it's

own fader (slider) to adjust the volume of the channel's signal before it is

sent to the next stage (subgroup or master mix).

A slider is a potentiometer, or variable resistor. This is a

simple control which varies the amount of resistance and therefore the signal

level. If you are able to look into the inside of your console you will see

exactly how simple a fader is.

As a rule it is desirable to run the fader around the 0dB mark for optimum

sound quality, although this will obviously vary a lot.

Remember that there are two ways to adjust a channel's level: The input gain

and the output fader. Make sure the input gain provides a strong signal level

to the channel without clipping and leave it at that level — use the fader for

ongoing adjustments.

Subgroups are a way to "pre-mix" a number of channels on a sound

console before sending them to the master output mix. In the following diagram,

channels 1 and 2 are assigned directly to the master output bus. Channels 3,4,5 and 6 are assigned to subgroup 1, which in turn is

assigned to the master output.

Subgroups have many uses and advantages, the most obvious being that you can

pre-mix (sub-mix) groups of inputs.

For example, if you have six backing vocalists you can set up a good mix

just for them, balancing each voice to get a nice overall effect. If you then

send all six channels to one subgroup, you can adjust all backing vocals with a

single subgroup slider while still maintaining the balance between the

individual voices.

Note that if your mixing console's subgroups are mono, you will need to use

them in pairs to maintain a stereo effect. For each pair, one subgroup is the

left channel and the other is right. Each channel can be panned across the two

subgroups, while the subgroups are panned completely left and right into the

master output bus.

The main output from most mixing devices is a stereo output, using two

output sockets which should be fairly obvious and easy to locate. The

connectors are usually 3-pin XLRs on larger consoles, but can also be 6.5mm TR

(jack) sockets or RCA

sockets.

The level of the output signal is monitored on the mixer's VU meters. The

ideal is for the level to peak at around 0dB or just below. However you should

note that the dB scale is relative and 0dB on one mixer may not be the same as

0dB on another mixer or audio device. For this reason it is important to

understand how each device in the audio chain is referenced, otherwise you may

find that your output signal is unexpectedly high or low when it reaches the

next point in the chain.

In professional circles, the nominal level of 0dB is considered to be +4 dBu. Consumer-level equipment tends to use -10 dBV.

The best way to check the levels of different equipment is to use audio test tone. Send 0dB

tone from the desk and measure it at the next point in the chain.

Many mixers include a number of additional outputs, for example:

Monitor Feed: A dedicated monitor feed which can be adjusted

independently of the master output.

Headphones: The headphone output may be the same as the monitor feed,

or you may be able to select separate sources to listen to.

Auxiliary Sends: The output(s) of the mixer's auxiliary channels.

Subgroup Outputs: Some consoles have the option to output each

subgroup independently.

Communication Channels: Some consoles have additional output channels

available for communicating with the stage, recording booths, etc.